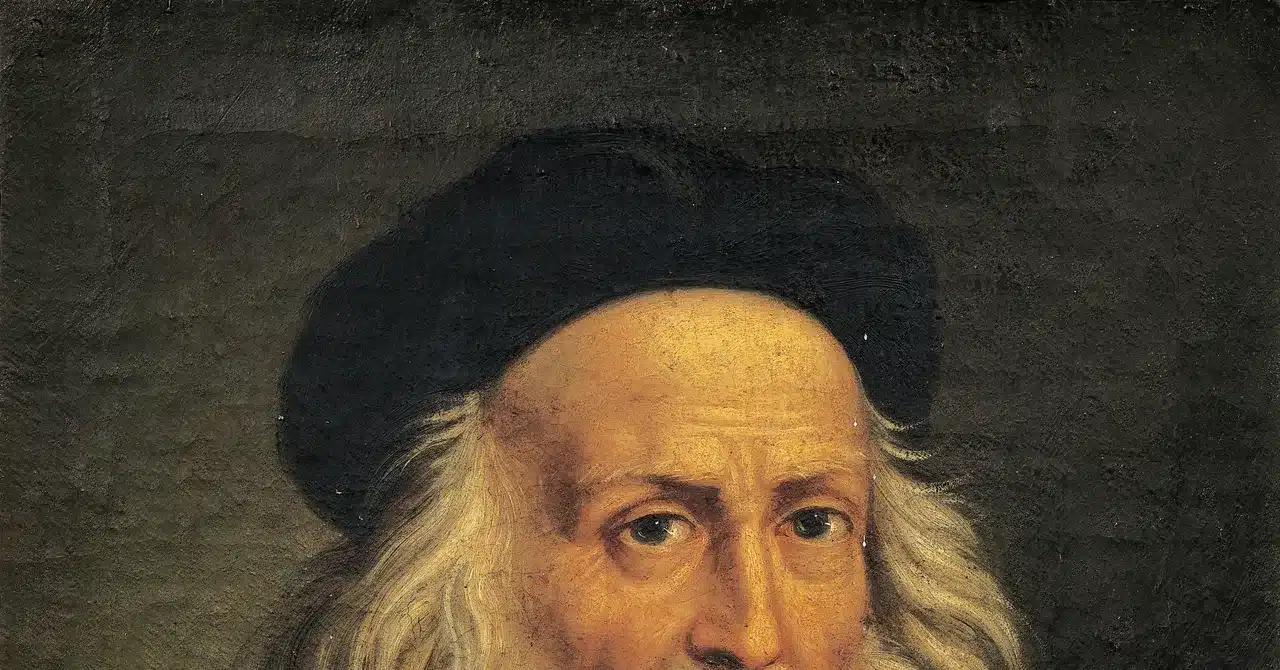

Researchers from the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project (LDVP) have reported an intriguing breakthrough in their analysis of the drawing of Holy Child and other Renaissance artifacts, including letters written by a relative of da Vinci. They discovered some Y chromosome DNA sequences that seem to belong to a genetic group with common ancestors in Tuscany, the birthplace of the Renaissance master in 1452. This could potentially mark the first instance of scientists identifying DNA that could be linked directly to da Vinci himself.

Historical artifacts can absorb DNA from their environment, which might shed light on the individuals who created and handled them. However, collecting this material from such precious objects without causing damage or contamination poses a significant challenge. Currently, the attribution of artworks relies heavily on expert judgments, like analyzing specific brushstrokes.

To tackle this, the LDVP researchers employed an incredibly gentle swabbing technique to gather biological material. They successfully extracted small quantities of DNA, yielding insightful results. “We recovered heterogeneous mixtures of nonhuman DNA,” the study, published in the preprint journal bioRxiv, notes, “and, in a subset of samples, sparse male-specific human DNA signals.”

Through their analysis, the researchers identified a close match within the broader E1b1b lineage on the Y chromosome, which is typically passed down almost unchanged from father to son and is found in regions of southern Europe, Africa, and parts of the Middle East. Some of this DNA might have belonged to Leonardo da Vinci.

“Across multiple independent swabs from Leonardo da Vinci–associated items, the obtained Y chromosome marker data suggested assignments within the broader E1b1/E1b1b clade,” according to the study. The results also revealed mixed DNA contributions connected to the source materials, likely due to modern handling.

“Together, these data demonstrate the feasibility as well as limitations of combining metagenomics and human DNA marker analysis for cultural heritage science,” the paper states, noting that this establishes a baseline workflow for future conservation efforts and investigations related to provenance, authentication, and handling history.

While the researchers have showcased an innovative method, they recognize that their findings are not conclusive. Although the data hints that the DNA could be da Vinci’s, confirming that any genetic material found in the artifacts belongs to him is quite complicated. “Establishing an unequivocal identity … is extremely complex,” said David Caramelli, an anthropologist from the University of Florence and a member of the LDVP.

The challenge arises because scientists can’t compare the genetic sequences from the artifacts to any DNA samples confirmed to be from Leonardo himself, as no verified samples exist. Additionally, da Vinci had no known direct descendants, and his burial site was disturbed in the early 19th century. Inspired by this initial clue about da Vinci’s DNA, LDVP researchers are now eager to persuade the caretakers of Leonardo’s artworks and notebooks to allow further sampling that may help solve this historical mystery.

This story originally appeared in WIRED Italia and has been translated from Italian.