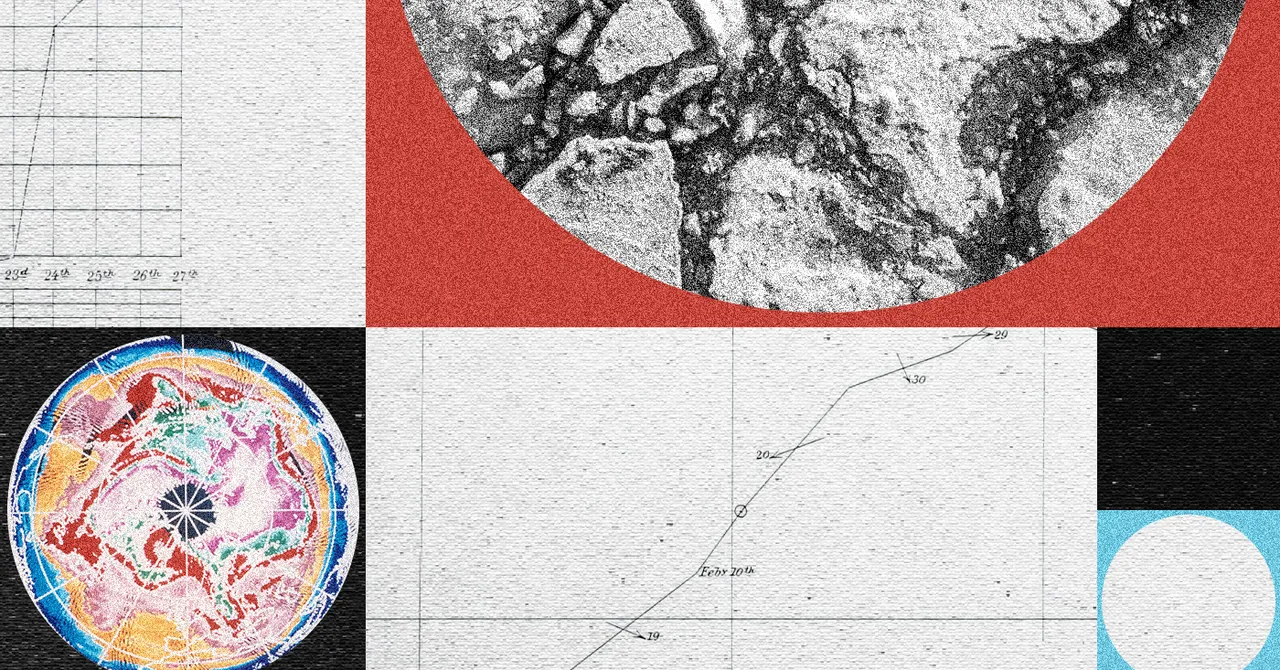

Since 2018, researchers globally have been analyzing how much heat the world’s oceans absorb each year. In 2025, they reported record-breaking measurements for the eighth consecutive year, showing that the oceans absorbed more heat than in previous years. This study, published on Friday in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Science, revealed that the world’s oceans took in an additional 23 zettajoules of heat in 2025—the highest amount recorded since modern measurements began in the 1960s. This figure is notably greater than the 16 additional zettajoules absorbed in 2024. The research team comprised over 50 scientists from the United States, Europe, and China.

To put these figures into perspective, a joule is a standard unit of energy, comparable to the energy needed to power a small lightbulb for about a second or slightly elevate the temperature of a gram of water. However, a zettajoule equals one sextillion joules. The 23 zettajoules that the oceans absorbed can be expressed numerically as 23,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

John Abraham, a professor of thermal science at the University of St. Thomas and one of the paper’s authors, sometimes finds it hard to relay these massive numbers in relatable terms. His favorite analogy equates the energy absorbed by the ocean to that of atomic bombs: The warming observed in 2025 is similar to the energy released by 12 Hiroshima bombs exploding in the ocean. Other comparisons he’s made include the energy needed to boil 2 billion Olympic swimming pools or more than 200 times the total electricity usage of everyone on Earth. “Last year was a bonkers, crazy warming year—that’s the technical term,” Abraham quipped. “The peer-reviewed scientific term is ‘bonkers’.”

The oceans serve as the planet’s largest heat sink, absorbing over 90 percent of the excess warming trapped in the atmosphere. While some of this heat raises the ocean’s surface temperature, it gradually penetrates deeper areas, aided by ocean currents and circulation.

Global temperature calculations, which help identify the hottest recorded years, generally only consider surface temperature measurements. Interestingly, the study found that sea surface temperatures in 2025 were slightly lower than in 2024, which holds the record for the hottest year since modern records began. Meteorological events like El Niño can elevate surface temperatures in certain areas, resulting in the ocean absorbing slightly less heat in specific years. This phenomenon helps clarify the significant increase in ocean heat content between 2025, which ended with a weak La Niña, and 2024, following a strong El Niño.

Although sea surface temperatures have risen since the industrial revolution due to fossil fuel usage, these surface measurements don’t fully capture the impact of climate change on the oceans. “If the whole world was covered by a shallow ocean just a couple feet deep, it would warm at a similar rate to land,” explains Zeke Hausfather, a research scientist at Berkeley Earth and a coauthor of the study. “However, because so much heat is being absorbed by the deep ocean, we observe a generally slower increase in sea surface temperatures compared to land temperatures.”